Did you know that Cape Cod has nearly 1,000 freshwater ponds? The Cape’s natural ponds are the result of the glaciers that left this area 18,000 years ago. Chunks of glacial ice gouged depressions into the substrate, creating “kettle ponds” that are recharged by rain and melting snow. Precipitation saturates the sandy substrate beneath us some 300 feet deep above bedrock. The groundwater that fills these ponds is the same water we use for our drinking water and irrigation. This water connection is why our ponds are called “windows on our aquifer.”

Most ponds, unaltered by development, are ringed by native woody shrubs like buttonbush, high bush blueberry, and winterberry. These shrubs grow in moist areas, but do not want to be submerged, so the annual high-water level keeps them within a defined edge. Fallen trees and overhanging shrubs give shade, help moderate water temperature in summer months, and provide cover for fish and sunning spots for turtles.

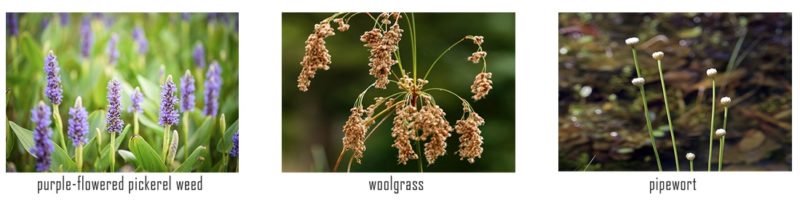

In the shallows of the water, you will find emergent plants like pickerelweed, with its spade-like leaves and purple flower spikes, a favorite of bumblebees. There may be rushes and reeds like woolgrass and pipewort. Submergent plants found in deeper water may include spatter dock, with golden globe-shaped flowers amid large flat leaves, and native white water lilies. Their summer leaves also give shade and help moderate temperature, minimizing algal growth and forming a microhabitat for insects, both above and below the leaves. Fish hide from great blue herons and feed on algae and smaller swimming creatures. Small birds land on floating vegetation to catch an insect or have a drink. The submerged portions of all aquatic plants provide habitat value for numerous invertebrates that are food for fish, ducks, and other wildlife. As fall temperatures arrive, pond vegetation dies back, falling beneath the water’s surface, where the plants’ nutrients are recycled through decomposition.

The water levels in most Cape ponds fluctuate due to changes in groundwater, precipitation, evaporation, and sometimes drawdown by municipal wells. When the shoreline becomes exposed, a coastal plain pond plant community may thrive if it is not trampled or the shoreline otherwise altered by beach fill or structures. This globally threatened habitat of a specialized plant community consists of rose tickseed, grass-leaved goldenrod, Plymouth gentian, and sandplain agalinis. These plants have adapted to the Cape’s kettle ponds, which historically have been low-nutrient, acidic glacial ponds with sand or gravel bottoms.

What plants do you see when you hike around our ponds? Do you see any of these? Tag us on Facebook so we can see!

Pond Stories are a collection of writings and other media from Cape Codders and visitors who love the almost 1,000 local ponds that dot the Cape. We hope this collection of stories awakens your inner environmentalist to think deeper about our human impacts to these unique bodies of water.

Send us your favorite pond photo, story, poem, video, artwork – we want to share with everyone why the Cape’s ponds and lakes are so special. Email your pond connection to [email protected]